Brass

Welcome to Lancashire, England in the 18th Century.

The world is about to change from Medieval to Modern; the change will come to be known as the Industrial Revolution. Can you take advantage of this time of transformation? What’s the best strategy for success? Build cotton mills? Develop new technologies? Dig canals? Produce coal, or maybe steel? There is no simple answer and the opportunities that arise will be different in each game you play as you move through the Canal and Railway periods, striving to get the best return you can from your investments – just in time to snatch the next opportunity from under the noses of your rivals.

Brass is a tactical game where you make money to make more money. However, you also need to ensure that the industries you create are sustainable, making Brass unique and endlessly fascinating. It’s an excellent game for experienced and dedicated game players as well as those interested in strategic multilayered games of history.

User Reviews (11)

Add a Review for "Brass"

You must be logged in to add a review.

Brass is a great game. It really is. It just takes a while to appreciate that fact. It is not an easy game to pick up. You’ll have to suffer through some confusion and likely losses to finally get that “Aha!” moment.

Played over two Ages, it’s all about managing your income and funds to build structures (tiles) which will provide you with coal, iron, and other means of scoring victory points and raising your income level.

Your stacks of tiles must be kept in a certain order, however, and you are able to spend actions to discard from the tops of them, so that you can reach the deeper, more lucrative ones. You’re also limited in where on the map you can build, because you’ll have a hand of cards which will either match a city, or a type of building. Spots tend to fill quickly, leading to late-game “Stomping”, or building over your opponents tiles to steal those points.

At the end of the first age, the Canal Era, low-point buildings are removed from the board, paving the way for the Railroad Era to begin. This changes the dynamic of the board, opening routes that previously did not exist. It also means you’re faced with the decision of whether to build cheap buildings early on, to boost your income and score a few points, but then lose those buildings at the midway point, or save up, discard some tiles, and build more expensive ones which will stay around for the whole game.

This is definitely a brain-burner. It can tend towards Analysis Paralysis if you’re the type to lean that way. There are a lot of options available to you, and fiddling with your money and loans is a huge part of the game.

That said, if you have the time and interested friends, this is a great afternoon or evening.

Pros:

Very fun game

Nice components, slick cards

Cons:

Brain burning!

Difficult to teach

Taking place in the industrial revolution in England, Brass immerses the players in the role of budding Industrial giants. Individual businesses, transportation networks, and personal fortunes rise and fall as England races towards modernization. As the modern age dawns, the player who has best laid the groundwork of a vast business empire will ride into the future with vast sums of money, winning the game.

From the winning condition of the game, it is important to note that the winning condition isn’t necessarily having the most money, taking this out of the genre of a pure economic game. Rather, the purpose of the game is to have the largest industrial footprint on the map, to be the most influential tycoon. Preparing for the future is the theme which carries the game forward. This theme is driven in not only by the winning condition, but through the idea of two “ages” in the game, the loan system, and the importance of balancing an empire on the point of disaster to emerge stronger down the road.

Mechanically, cards drive Brass. This might be a critical flaw for players that cannot stand an element of chance in a 2-3 hour heavy strategic game, and I will warn those players away from this game. For those who do not mind this so much, it adds a great amount of re-playability a game which might otherwise be too rigid to be interesting. The cards drive the central actions of the game which are:

– Establish an industry

– Take a loan

– Develop towards more advanced industries

– Ship cotton

– Build canals/rails

These actions are taken by playing a card, two per turn. Most of which are in a player’s hand at the beginning of each of the two ages (canal and rail). These cards, not money, are the real currency of the game to experienced players. Once an action is taken, a new card is drawn until the deck is exhausted, at which point no further loans may be taken. Remaining cards are then played until none are left, advancing the game to the next age or ending the game. Without getting into too much detail, each card imposes limits on where an industry may be established. This makes forward-planning and hand management a critical aspect of the game; players must tactically react to opportunities which arise through game-play, but largely adhering to a strategy is necessary to do well. To allow opportunistic play, two cards may be played to take any action, ignoring limitations.

To establish a business, a player has two options:

– Play a card of the city the new business is to be established in.

– Play a card of the specific industry in any city only if the player’s transportation network is connected to it.

These limitations of what businesses can be established and where are the source of the hand management in the game. Useful cards must be coveted, while others may be dumped on all other actions. Further, the map of England has limitations, as seen on the icons on the map, of what types of businesses may be established in each city, and how many of each. Finally, businesses must be paid for with cash and connected resources (iron and coal).

Once a business is established, it must establish itself in the existing economy and become profitable before it advances a player towards victory. Cotton must be shipped to either the foreign market or in the local ports. Ports must establish regular clients from the cotton industry. Coal mines and iron works must establish customers which use the resources they provide. Successfully maturing a business will provide a player with extra income and victory points.

Finally, transportation networks connect these industries, opening the means to ship goods to potential clients. Cotton and coal cannot travel outside of their source city without a player having invested in the infrastructure to move it in large quantity. Iron, because it represents a one-shot building expenditure rather than a constant series of shipments, does not suffer the same limitation and may move freely about the map.

I mentioned before that the game has two ages. Once the beginning canal phase is completed, all canals are removed from the game, as are obsolete businesses. More advanced businesses remain on the board, setting the terrain for the second age to begin. Wise players will have prepared themselves for this transition and quickly extend vast rail networks. Still others may have created several coal mines at the end of the canal age to provide these rail tycoons (or themselves) with the means to create a rail empire.

Through the mechanisms of establishing industries, building infrastructure, and establishing profit, the players will create a functioning economy. The players will both compete and cooperate by finding niches in the supply and demand cycles that arise. If other players are competing in cotton mills, for instance, a player may wish to invest in ports to provide a means for them to ship their products. It’s this interaction that makes Brass great.

While this is hardly an exhaustive list of the rules of Brass, it provides enough framework to get a general idea of how the game flows. The historical immersion of Brass is surprisingly rich as players witness the interactions of their business empires creating a living, breathing economy. By finding niches, seizing opportunities, interacting with competitors, and sticking to his guns, a player will find themselves on top.

When it comes to complicated games, Martin Wallace is a master! But he’s also excellent at creating highly balanced and good games. Brass is one of those games, but it does have its caveats.

What you do in this game is expand and build factories or other production buildings. When upgrading them, you gain points depending on the connection to other players and a harbor that hasn’t been used yet. But in order to place a factory, there are several requirements that needs to be fullfilled.

You have a hand of cards which allows you to build certain buildings, like harbor, mining facility and more. But you can’t play them anywhere, they have to connect. And it’s rarely easy to find a location which benefits only yourself, but you have to do something. So the game flow is simple enough.

But regarding rules, there’s a lot more to consider. To place one of these buildings, there are so many things to take into account. So many, that it might be overwhealming for some. And when you finally think you’ve figured it out, there’s something new to learn to prohibit you from doing what you want.

This is a good game, but it needs to be played once just for the training. The next game would be more fair. Experience here is key. Also, the game can last for a couple of hours or maybe more.

If you like heavy brain burning and good planning games, then this is for you. If you’re in for more casual play with your friends, this isn’t one to pick up. It requires dedication from all players.

Brass is a lot of fun, if you’re looking for a deep game with a lot of strategy, that may leave your head hurting (but in a good way, or at least so say people I’ve played with).

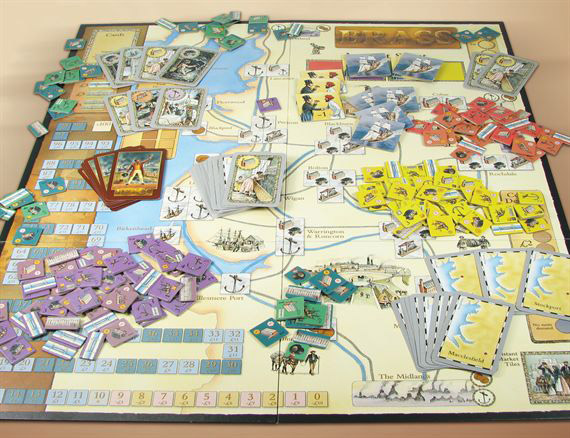

You’re building up a network of industries over two ages in Lancashire, England in the 1700’s. First, the canal period, where cities are connected by waterways to transport the cotton, iron, coal. In the second period, the canals are gone, ready to be replaced by a railroad network, opening up different connections. Scoring occurs twice, at the end of each round.

To build, you are using cards you are dealt or have drawn which either show an industry, or a city. Each round you get two actions. Additionally, you have stacks of different industries (cotton mills, coal, iron, ports, and ships) which have different levels. The higher the level, the more points they’ll score, but they are more expensive and require more resources to get out (resources which you must be linked to via canals/railroads/markets). You don’t get access to your higher level industries until after your lower level ones. You can also pay (iron) to develop away lower level industries, but it takes actions to do so. Turn order is determined by how much money players spent the previous round, lowest spender going first.

On each of your turns, you’re balancing your actions. You can:

Build Industries

Build Canal/Track

Develop away Industries

Take a Loan

Play two cards to do one action

Pass

There are many strategies one can play. Which one(s) you go after will be determined by your hand, what other players are doing, and experience. Brass is not a game that a first-time player should sit down to expecting to win. To understand the nuances, it’ll take experience playing the game.

Brass falls on the heavier end of complexity, with a number of easy to miss rules, and a lot of strategy. I would not recommend Brass for non-gamers. If you’re looking for a challenging and rewarding gaming experience that can be very competitive, Brass may be for you. If you decide to give it a try (and I hope you do!) I’d recommend either reading the rules, or watching video reviews to get an idea of what you’re going into before playing. Bringing along a player aid will help as well. Learning the rules of Brass can be very cumbersome, but in my opinion, the game play makes it worth the effort!

Brass is an incredibly well-designed game that is absolutely packed with choices and long term decisions. This is a game that has multiple strategies and will take many many plays to master. If you like to think and plan and scheme, this is a game to look into.

In Brass, each player is an industrial tycoon in pre/post Industrial England. There are towns throughout the board that are connected by routes and have slots to produce coal, cotton, provide shipyards, ports, etc.

Each player has a hand of 8 cards. On your turn, you play one card from your hand, then refill it. The round (there are two rounds total) ends when all cards are played.

There are two types of cards: One that specifies a type of building (i.e. Coal). It can be played on ANY town with a coal plant to which you already have an adjacent building. The other card type specifies a town. You can build ANY building in this town that the town supports.

Placing a building cost money and provides you with some of the resources. For example, buying a coal building provides a few cubes of coal, which can be used to build other buildings. Once all the coal on the coal building is used, you flip it over for points. The other fun thing is that other players can use your coal, which is just fine as it means THEY are giving YOU points.

You have limited stacks of each building in multiple levels. The higher level ones cost more (coins and resources), but provide more points. On your turn, you can also play a card to build canals/railroad (depending on the phase) OR you can develop, which means you discard buildings. You might discard a building to instead get to the more valuable buildings more quickly. This is a KEY advanced strategy.

Finally, you can use your turn to take a loan.

This is a game that requires so much thought! Your opponents will build the building you wanted to build, or they’ll place a building to block you (remember, adjacency is important). Or, they’ll buy the coal you were hoping to use. You’ll see one player sprinting to build the incredibly valuable shipyards…can you block him in time?

Over the course of the two rounds much thought will be had.

I have two problems with the game, which may not be problems for some. For one, the game takes at least 2 hours to play, which means it’s difficult to get to the table. Secondly, the canal phase seems a bit…unnecessary. What I mean is that I feel the game could have been streamlined into a single phase, which is apparently what the designer did with another game.

Overall, this is a beautiful, incredibly well-designed game. It’s one of the few really difficult, brain-burny games I enjoy and I think it deserves a spot in your collection if you have any interest in such a game.

Summary

Brass puts you in the shoes of a magnate of the industrial revolution in North West England. Want to build a business empire? With canals? And railways? This is your game!

This is not a “railway” game in that the main aim of the game isn’t to create a transport network. Rather you will spend the game developing and building industries, which may need those connections to either be built or become profitable.

How does it play?

The game is split into two halves. The first canal era involves you placing lower level industries and linking them with canals. The second rail era involves you placing more advanced industries and linking them with rails. The canals you place in the first era are removed in the changeover, representing them being at capacity.

Depth wise Brass is a heavy game. There is a huge amount of strategy here and you can really benefit from thinking a few turns ahead. You won’t be able to think more than that as there are too many variables from other player actions and too much information on the board to perfectly process. Not that this wont stop some players trying, so I suggest holding turns to a time limit (an egg timer or little hour glass works perfectly).

Mechanically, Brass is actually not heavy at all. It is elegantly designed and is intuitive despite the complexity. Turn order is as follows:

1. Look at the income track for each player, so each player receives / pays in cash from / to the bank.

2. In player order, each player plays two of their eight cards (as to what they can do, see below).

3. Reset player order based on cash spent (the first player is the most frugal – not that this is always an advantage).

4. Each player draws two more cards (if available).

The game ends at the ends of the rail era, and each era ends when players don’t have any cards left to play.

So what can you do with the cards? Well, with the exception of establishing an industry, which is limited to an industry in the place depicted on the card or of the type depicted on the card, anything. In this way, Brass is actually a bit like a worker placement game – you have freedom to do with each card whatever you want, whether it is taking a loan to pay for more industry buildings, developing higher level industries, building canals or rails, or shipping cotton to advance up the income track.

Pros

– Depth without rules overload

– You end the game feeling like you really are an industry tycoon

– Great replayability

Cons

– Board could be more colourful

– Analysis paralysis can be an issue

TL;DR

Mechanically simple but deep industrial revolution tycoon style game.

Martin Wallace’s ‘Brass’ is one of those games that you tend to think about even when not playing. The rulebook is well-written, and its material components are handsomely produced. It’s easy to return to. Which is good, because,as with the best euros, repeated plays of ‘Brass’ reveals deeper and deeper layers of strategic possibility.

Mechanically speaking, it never feels overburdened by chrome or by needless knobs, dials, or other assorted doohickies. And though it doesn’t play fast (clocking in at about 2 hours), ‘Brass’ does offer a very *smooth* ride, especially impressive for a heavy economic game set during England’s industrial revolution.

I love how the game is played out over two historically distinct phases. Overall, it creates a palpable sense of developmental ebb-and-flow in which market timing becomes a premium concern. The other major concern, which of course is signature Wallace, is all about finagling market access by building up clever networks of canals and later railways. Delicious decisions abound, many relating to cash-flow: how many loans will be too many?–And to what extent will you be willing to benefit another player by leveraging a shared network?

‘Brass’ is a wonderfully interactive game. It is also a very good example of a game whose mechanics and structure are expertly integrated with its theme and setting. If you like economic games and clever simulations of history, it will be difficult to find a better game.

It took us a while to crack Brass, but our group had a lot of fun along the way. It has a good simplified market system that creates market opportunities – not in a contrived way – but as a side effect of things you are trying to do in the game. After several plays, we discovered that setting up a big rail move at the beginning of the second era is vital. Several plays more and we were all pretty good at optimizing this move – which turned 5-6 moves of the game into almost programmed sequence of getting loans, jockeying for turn order and making sure there is enough coal when you get into the rail age.

When we got to this point, we kind of stopped playing so often because at that point, the cards became too important to the outcome of the game.

We still play it every few months and now our skills have ebbed enough to make it more interesting.

Age of Industry looks like Brass, but since you rarely have very many cards, you don’t get much of a strategic look ahead. I will play Brass over AoI any day.

My experience with Brass goes something like this:

Oh, a new game!

Nice, that was good fun!

Wait. That was not fun. 🙁

— my overall impression was that it was a semi-complex planning game that didn’t have that whatever-it-is that makes you want to play it again. I mean, I could be convinced, if I was at a friend’s house and he was jonesing to play, but I honestly can’t imagine anyone jonesing to play Brass…

This is too complex for my time constraints. If you want to finish a similarly themed game, try Wallace’s Tinner’s Trail.

Thoroughly enjoy this game, even though it takes me a few plays to get back into the groove after being away for a while.